In the field of precision manufacturing, Titanium and Tungsten represent two of the most demanding materials to process. While both are valued for their extreme performance characteristics in aerospace, medical, and industrial applications, they present diametrically opposed challenges to the machinist.

Understanding the fundamental differences between these elements is critical for process planning and cost estimation. Titanium is characterized by its high strength-to-weight ratio and chemical reactivity, often leading to issues with heat accumulation and material adhesion. In contrast, Tungsten is defined by its exceptional density and hardness, presenting challenges related to brittleness and abrasive tool wear.

A Crucial Distinction: Workpiece vs. Tooling

Before analyzing the machining parameters, it is necessary to clarify the scope of this comparison. This article focuses on Tungsten and its heavy alloys as workpiece materials (components used for counterweights, radiation shielding, or ballistics). This should not be confused with Tungsten Carbide (WC), which is the primary material used to manufacture the cutting tools themselves.

This guide provides a technical analysis of machining these two distinct metals, comparing their physical properties, common failure modes, and the specific strategies required to process them effectively.

The Challenges of Machining Titanium: Thermal and Mechanical Factors

Machining titanium alloys (such as the ubiquitous Ti-6Al-4V) presents a unique set of tribological and thermal challenges. Unlike ferrous metals, titanium’s machinability is governed by its inability to dissipate heat and its tendency to chemically interact with cutting tools. The primary difficulties can be categorized into three physical mechanisms:

1. Thermal Concentration at the Cutting Edge

The most significant barrier to processing titanium is its extremely low thermal conductivity (approximately 6.7 W/m·K for Grade 5 Titanium, compared to roughly 50 W/m·K for carbon steel). In standard machining operations, the majority of the heat generated is typically carried away by the ejected chips. However, due to titanium’s poor conductivity, this heat transfer mechanism is inefficient. Instead, thermal energy accumulates rapidly at the tool-workpiece interface. This thermal concentration can lead to premature tool failure through plastic deformation of the cutting edge and accelerated crater wear.

2. Chemical Reactivity and Galling

Titanium exhibits high chemical reactivity with tool materials (such as carbides and ceramics) at elevated temperatures. This property leads to a phenomenon known as galling or cold welding. During the cutting process, titanium material tends to adhere to the cutting edge, forming a Built-Up Edge (BUE). This adhesion compromises surface finish and can cause chipping of the tool insert when the welded material breaks away. In shop floor terminology, this behavior is often described as “gummy,” referring to the material’s tendency to smear rather than shear cleanly.

3. Low Modulus of Elasticity and Springback

Titanium has a relatively low modulus of elasticity (Young’s Modulus) compared to steel ($110 \text{ GPa}$ vs. $210 \text{ GPa}$). This implies that titanium is more flexible and prone to deflection under cutting pressure. As the tool engages, the workpiece may deflect away from the cutter and then “spring back” once the pressure is released. This elasticity causes two primary issues:

- Chatter and Vibration: The instability can lead to regenerative chatter, reducing tool life and surface quality.

- Dimensional Inaccuracy: The springback effect makes holding tight tolerances difficult, as the material may rub against the tool flank rather than being cut.

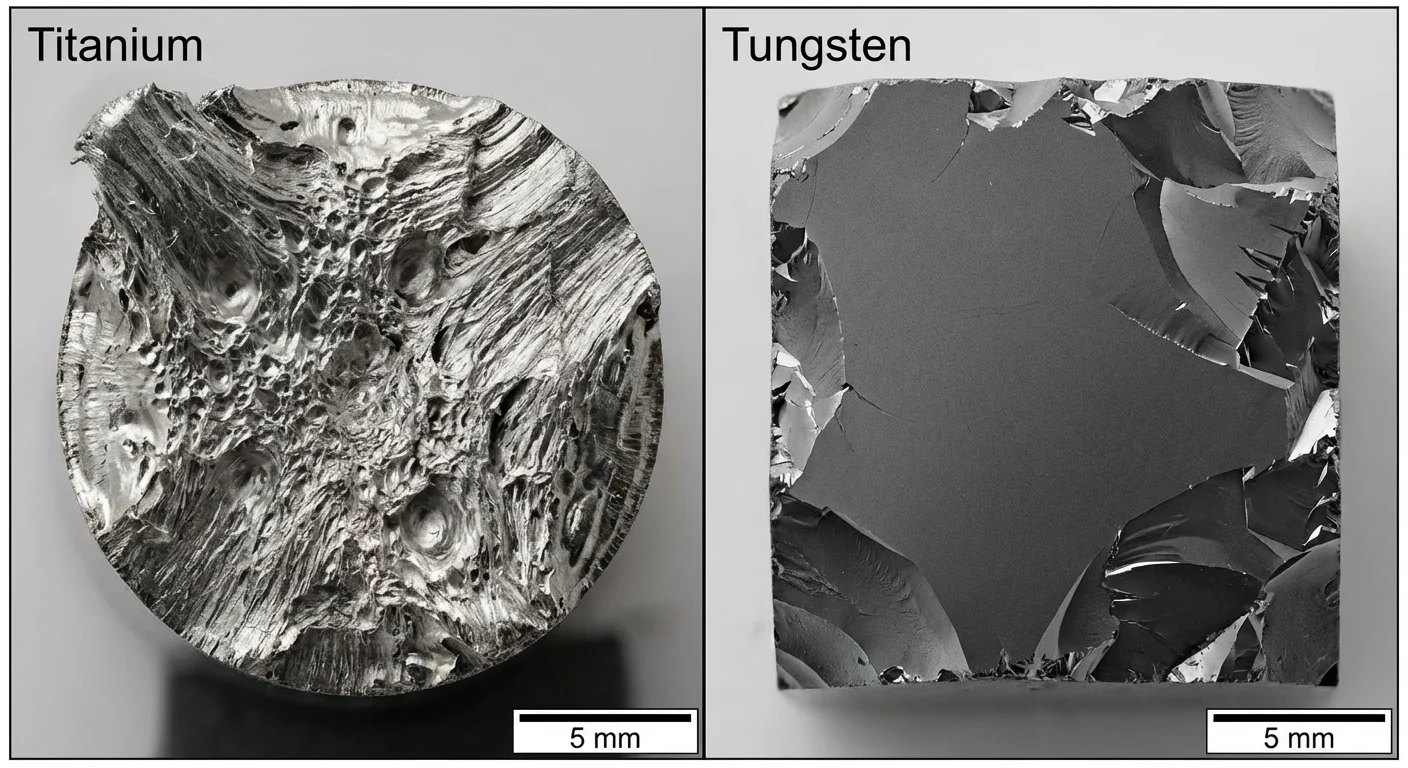

The Challenges of Machining Tungsten: Brittleness and Abrasive Wear

While titanium challenges the machinist with heat and elasticity, tungsten presents a fundamentally different set of obstacles rooted in its density, hardness, and manufacturing origin. The machining behavior of tungsten is often compared to that of gray cast iron or ceramics, primarily due to its lack of ductility.

1. Sintered Structure and Grain Pull-out

Unlike titanium, which is typically cast or forged, tungsten components are often produced via powder metallurgy (sintering). This means the material is composed of compressed and fused metal grains rather than a continuous crystalline structure. During machining, especially with pure tungsten, the cutting forces can cause individual grains to dislodge rather than shear smoothly. This phenomenon, known as grain pull-out, leads to a pitted surface finish and can accelerate tool wear.

2. High Hardness and Abrasive Wear

Tungsten and its alloys exhibit exceptional hardness (typically 30-40 HRC for alloys, and higher for pure forms). This results in severe abrasive wear on the cutting tool. Unlike the crater wear seen in titanium caused by heat and chemical reaction, tungsten wears down the tool flank physically. The material acts as an abrasive against the cutting edge, necessitating the use of extremely hard tool substrates, such as Polycrystalline Diamond (PCD) or specific grades of Tungsten Carbide (C-grain) to maintain dimensional accuracy.

3. Low Fracture Toughness and Brittleness

The most critical risk when machining tungsten is its brittleness (low fracture toughness). Tungsten has very little capacity for plastic deformation.

- Entrance and Exit Failure: The material is prone to chipping or “breakout” when the drill or milling cutter exits the workpiece. The lack of support at the edge causes the material to fracture rather than cut.

- Structural Integrity: Improper fixturing or excessive cutting pressure can cause the entire workpiece to crack or shatter, similar to glass.

4. The Distinction: Pure Tungsten vs. Heavy Alloys

It is important to differentiate between Pure Tungsten and Tungsten Heavy Alloys (WHAs).

- Pure Tungsten: Extremely brittle and difficult to machine. It often requires heating the workpiece to above its ductile-to-brittle transition temperature (DBTT) to process effectively.

- Tungsten Heavy Alloys (W-Ni-Fe or W-Ni-Cu): These alloys contain a binder phase (Nickel, Iron, or Copper) that encapsulates the tungsten grains. This binder provides a degree of ductility, making WHAs significantly more machinable than their pure counterpart, though they remain challenging compared to standard steels.

Quantitative Comparison: Physical Properties and Machining Implications

To optimize process parameters, engineers must look beyond qualitative descriptions to the fundamental material properties. The following table contrasts Titanium (Grade 5, Ti-6Al-4V), the most common titanium alloy, with Tungsten Heavy Alloy (Class 1, 90% W), a standard specification for machinable tungsten.

| Property | Titanium (Ti-6Al-4V) | Tungsten Heavy Alloy (90% W) | Machining Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density | 4.43 g/cm³ | 17.0 – 18.5 g/cm³ | Workholding:Tungsten parts have high mass inertia. Fixturing must account for centrifugal forces in turning operations. |

| Hardness | 30 – 36 HRC | 24 – 32 HRC (Matrix)* | Tool Wear:Tungsten causes abrasive wear due to hard grains; Titanium causes adhesive wear/galling. |

| Young’s Modulus (Stiffness) | 114 GPa | ~360 GPa | Deflection:Titanium is flexible (prone to chatter). Tungsten is extremely rigid (prone to fracture if clamped on uneven surfaces). |

| Thermal Conductivity | 6.7 W/m·K | ~100 W/m·K | Heat Management:Titanium traps heat at the tool tip (requires coolant). Tungsten dissipates heat well but generates high friction heat. |

| Machinability Rating | ~20% (of B1112 Steel) | ~10-15% (of B1112 Steel) | Speed:Both require significantly reduced surface speeds (SFM) compared to steel. |

*Note: The hardness of Tungsten Heavy Alloys refers to the composite hardness. The individual tungsten grains within the matrix are significantly harder, contributing to the abrasive nature of the material.

Interpreting the Data for Manufacturing

Two critical disparities from the table dictate the machining strategy: Elastic Modulus and Thermal Conductivity.

- Rigidity vs. Elasticity: Tungsten is approximately three times stiffer than Titanium. This high modulus means Tungsten will not deflect away from the cutter, allowing for better dimensional control—provided the tool does not break. Conversely, Titanium’s low modulus requires “positive” cutting actions; the tool must cut, not rub.

- Heat Dissipation: The drastic difference in thermal conductivity dictates the coolant strategy. For Titanium, the primary goal of coolant is thermal evacuation from the tool interface. For Tungsten, coolant is primarily used for lubrication and chip evacuation to prevent abrasive dust from re-cutting the surface.

Machining Strategies: Process Optimization

Successfully processing these materials requires a fundamental shift in machining philosophy. The strategies that work for one will likely lead to catastrophic failure for the other.

A. Strategy for Titanium: The “Shear and Cool” Approach

The primary objective is to manage heat generation and prevent work hardening.

- Climb Milling is Mandatory: Always employ Climb Milling (Down Milling). This ensures the tool enters the material cleanly at maximum chip thickness. In conventional milling, the tool rubs against the work-hardened surface before entering, generating excessive heat.

- High-Pressure Coolant (HPC): Standard flood coolant is often insufficient. High-pressure coolant systems (typically 1000 PSI / 70 bar+) delivered through the spindle are recommended to blast chips away and force fluid directly to the cutting zone.

- “Don’t Dwell” Policy: Titanium alloys are notorious for work hardening. Maintain a constant, aggressive feed rate. Never allow the tool to dwell or rub. If you need to pause, retract the tool immediately.

- Positive Tool Geometry: Use inserts with high positive rake angles to “shear” the metal with minimal cutting force. Coated carbides, particularly Aluminum Titanium Nitride (AlTiN), are preferred.

B. Strategy for Tungsten: The “Rigid and Abrasive” Approach

The goal is to prevent fracture and manage abrasion.

- Absolute Rigidity: Vibration is the primary cause of failure. Use short, stout tool holders and ensure the workpiece is fully supported. Avoid thin-wall features whenever possible.

- Tooling Selection (PCD): Standard carbide tools degrade rapidly.

- Polycrystalline Diamond (PCD): For finishing cuts and tight tolerances, PCD tools are the industry standard to withstand abrasion.

- C-Grade Carbide: For roughing, use C-2 or C-3 grade carbide. Unlike titanium, tungsten often benefits from negative or neutral rake angles to protect the cutting edge.

- Temperature Management: While tungsten withstands heat, thermal shock can cause surface crazing. Coolant should be used for dust control. Air blast is sometimes preferred if thermal shock is a concern.

- The Non-Contact Alternative (EDM): Given the difficulties of mechanical removal, Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM)—both Wire and Sinker—is often the most efficient method for complex tungsten geometries, completely eliminating mechanical stress.

The Economics of Precision: Cost Drivers Breakdown

When quoting or planning for these materials, the final cost is driven by different factors. Understanding where the money goes helps in accurate budgeting.

1. Titanium Cost Driver: Time and Material Waste

- Cycle Time: Due to the requirement for low surface speeds (SFM) to prevent heat buildup, machining titanium is inherently a slow process. A part that takes 10 minutes in aluminum might take 60 minutes in titanium.

- Buy-to-Fly Ratio: In aerospace, parts often start as large billets with significant material removal. While swarf is recyclable, the processing time to remove it is substantial.

2. Tungsten Cost Driver: Tooling and Risk

- Consumables: Tungsten consumes cutting tools rapidly. The cost of frequent insert changes and premium PCD tooling inflates operational costs.

- Scrap Risk (The “Fear Factor”): Tungsten raw material is expensive. Because the material is brittle, there is a high risk of the part shattering during final finishing. Shops often factor in a risk premium to cover potential scrap.

FAQ: Common Engineering Inquiries

Q: Is Tungsten harder to machine than Titanium?

A: Yes, generally speaking. Tungsten is significantly harder and abrasive, leading to rapid tool wear. However, Titanium is often considered “trickier” due to its reactivity and tendency to gum up the cutter. Tungsten requires patience and hard tools; Titanium requires thermal management and sharp tools.

Q: Can you tap threads in Tungsten?

A: Tapping holes in tungsten is extremely risky and often results in broken taps. For threaded features, thread milling is highly recommended as it produces lower cutting forces. Alternatively, using EDM to create threads is a safer option.

Q: Why is Titanium swarf considered dangerous?

A: Titanium chips, particularly fines, are highly flammable (Class D fire hazard). The high heat generated during machining can ignite the chips. Shops must have dedicated fire suppression systems and proper housekeeping protocols.

Conclusion: Choosing the Right Approach

The battle between Titanium and Tungsten is not about which material is “better,” but rather which physical laws must be respected.

- Titanium demands a strategy of “Shear and Cool.” It requires sharp, positive tooling, high-pressure coolant, and aggressive feed rates.

- Tungsten demands a strategy of “Rigidity and Patience.” It requires stiff setups, abrasive-resistant substrates, and a process that treats the metal more like a ceramic than a steel.

For engineers and machinists, success lies in acknowledging these unique material personalities. By tailoring the coolant, tooling, and tool paths to the specific properties of the workpiece, even these “impossible” metals can be machined with precision and predictability.