Titanium is every engineer’s dream metal. It matches the strength of steel while being 45% lighter, and it possesses an almost supernatural resistance to corrosion. However, for the welder tasked with joining it, titanium can quickly become a nightmare.

Unlike steel or aluminum, titanium has a unique and dangerous characteristic at high temperatures: it acts as a “Universal Getter”. Once the metal heats past 800°F (427°C), it behaves like a sponge, aggressively absorbing oxygen, nitrogen, and hydrogen from the atmosphere. If this absorption occurs, the weld doesn’t just look ugly; it transforms into “Alpha Case”—a brittle, glass-like structure that inevitably cracks under stress.

Welding titanium isn’t just about hand speed or puddle control; it is fundamentally an exercise in environmental control. Whether you are fabricating a custom exhaust for a race car or welding Grade 2 piping for a chemical plant, the physics remain the same. This guide explores the critical steps required to achieve that perfect silver weld and avoid expensive scrap.

Obsessive Preparation (The “White Glove” Rule)

If you approach titanium with the same mindset used for stainless steel, you have already failed. A successful titanium weld is determined almost entirely by what happens before the arc is struck. You must adopt a “cleanroom mindset,” regardless of whether you are working at an aerospace hangar or a fabrication shop.

The process begins with chemical purity. Before any mechanical abrasion takes place, the base metal must be thoroughly wiped down with industrial-grade acetone or methyl ethyl ketone (MEK). This step is non-negotiable because mechanical cleaning can drive surface oils deep into the metal’s pores if they aren’t removed first. Furthermore, the filler wire itself is often a hidden source of contamination. Filler rods sitting in storage collect dust and oxides. Seasoned professionals always run an acetone-soaked rag over the wire before welding, and you will be shocked at the black residue that often comes off.

Once the chemical cleaning is complete, the oxide layer must be removed using dedicated tools. A stainless steel wire brush or carbide burr should be used, but with a strict caveat: these tools must never have touched carbon steel. A brush that has previously cleaned steel will embed microscopic iron particles into the titanium, creating immediate corrosion points. From this moment on, the “White Glove Rule” applies. The part should only be handled with clean, lint-free nitrile gloves. Even a simple fingerprint contains enough oil to cause porosity and weld failure.

Equipment Setup & The “Big Cup” Strategy

You don’t need a million-dollar laser setup to weld titanium, but a standard TIG configuration suited for steel will likely fail. Success lies in optimising your machine and torch for maximum gas coverage.

The welding process must be DC TIG (GTAW) using DCEN (Direct Current Electrode Negative) polarity. This concentrates the heat into the workpiece rather than the tungsten, keeping the weld profile narrow. High-frequency (HF) start is mandatory; never use “scratch start” or “lift arc”, as touching the tungsten to the titanium results in instant contamination.

The “Big Cup” necessity: The standard collet body found on most torches creates turbulent gas flow, which pulls oxygen into the shield. You must upgrade to a gas lens system to organize the argon into a smooth, laminar flow column. Furthermore, standard ceramic cups (size #6 or #8) are far too small. To protect the reactive titanium puddle, you need a wide umbrella of gas. The industry secret is to use a #12, #14, or #16 (1-inch ID) cup—often referred to as a “BBW” cup. This massive coverage area is your best insurance against oxidation.

The Art of Total Shielding

In titanium welding, the arc is the easy part. The real challenge is protecting the hot metal after the arc has passed. Since titanium remains reactive until it cools below 800°F, you need to think in terms of three distinct layers of defense.

1. Primary Shield (The Torch) The first line of defense comes from your torch. With the large cup sizes recommended above, standard flow rates (15-20 CFH) are insufficient. You will need to increase your flow rates to 30-40 CFH to ensure the laminar flow remains robust.

2. Trailing Shield (The Tail) As your torch moves forward, the hot weld metal behind it is exposed to air while it is still above the critical 800°F threshold. For longer weld runs, a custom trailing shield attachment is often necessary. This device attaches to the torch and follows the weld path, blanketing the cooling metal with argon until it is safe.

3. Back Purging (The Root) Oxygen attacks from all sides. When welding tubing or pipe, the interior must be completely purged with argon. Aluminum tape is an effective tool for sealing pipe ends to trap the gas.

The “bad tank” reality: Ideally, you should aim for 99.999% (grade 5.0) purity of argon. While 99.995% is the absolute minimum industrial standard, be aware that small, owner-sized cylinders are often cycled less frequently and may contain impurities. If your setup is perfect but you still get blue welds, the tank might be the culprit. Additionally, upgrade to Teflon or braided hoses; standard rubber hoses can absorb moisture over time, raising the gas dew point and contaminating the shield.

Execution & Parameters

Before touching your expensive workpiece, there is one ritual that saves thousands of dollars in scrap: The Spot Test.

Never trust your gas supply blindly. Before welding, grab a piece of clean scrap titanium and run a few spot tacks. If the spot is bright silver, your system is ready. If you see a “rainbow halo,” blue tint, or haziness, STOP. You have a gas leak, moisture in the lines, or a bad batch of gas. Do not proceed until the spot test is perfect.

Welding Parameters Cheat Sheet Titanium generally requires less heat than steel. The goal is to weld as cool as possible.

| Material Thickness | Amperage (DCEN) | Torch Gas Flow* | Filler/Tungsten Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.040″ (1.0mm) | 30 – 50 A | 30 – 35 CFH | 1/16″ (1.6mm) |

| 0.063″ (1.6mm) | 50 – 80 A | 30 – 40 CFH | 1/16″ (1.6mm) |

| 0.125″ (3.2mm) | 90 – 120 A | 35-45 CFH | 3/32″ (2.4mm) |

Important Note: These flow rates (30-45 CFH) are specifically calibrated for #12 to #16 Large Gas Lenses. If you are forced to use a standard #8 cup (not recommended), reduce flow to 15-20 CFH to avoid turbulence.

Pro Tip: The “Double Post-Flow” Trick Titanium holds heat for a long time. If your machine’s post-flow timer ends before the metal cools (the standard 10 seconds is often insufficient for thicker parts), tap the pedal briefly to re-trigger the gas valve without striking an arc. Keep the torch stationary over the end of the weld until the color is safe.

The Verdict (Visual Inspection)

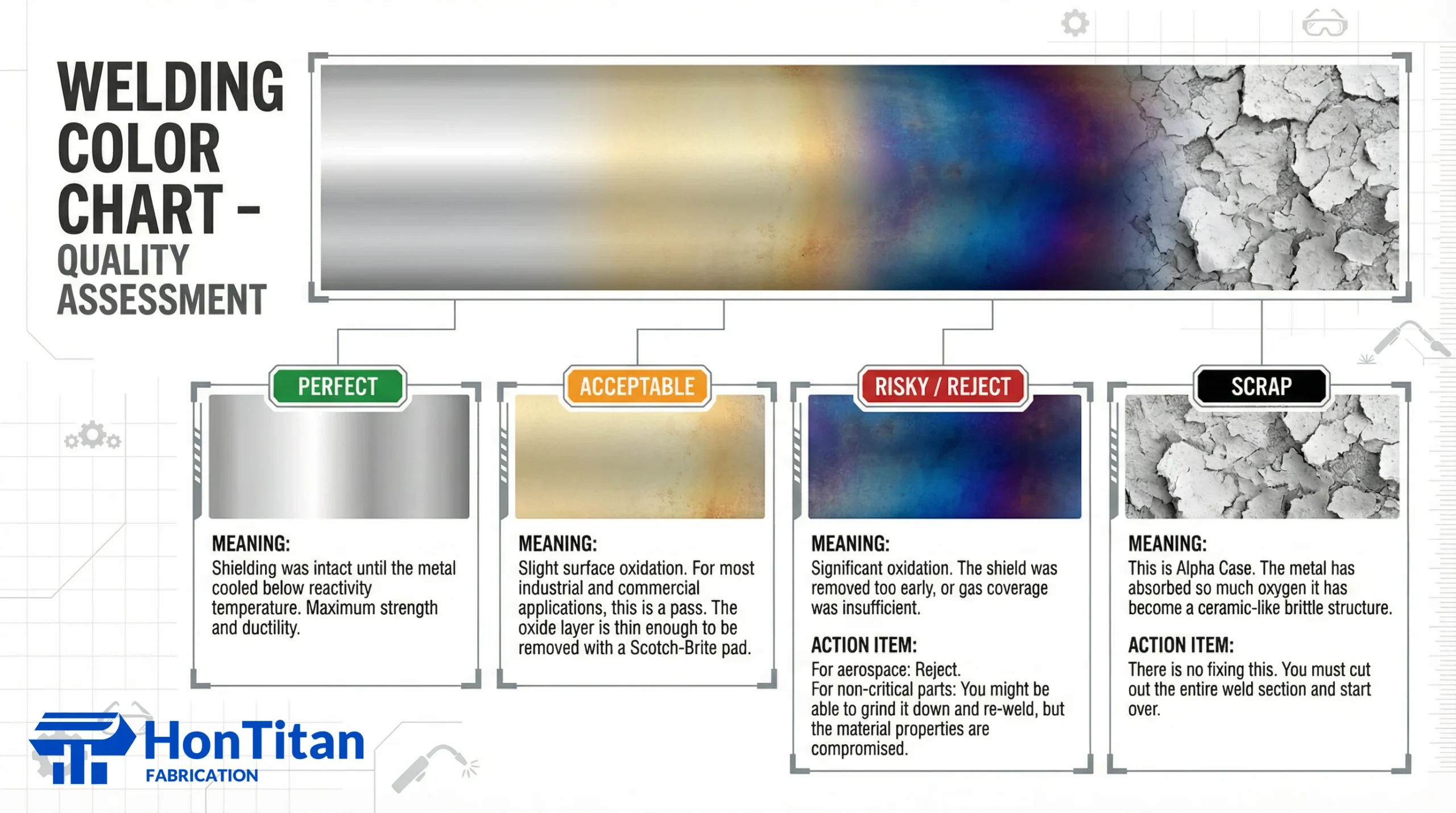

In the world of titanium, colour is your report card. The colour of the weld bead and the heat-affected zone (HAZ) tells you exactly how much oxide was absorbed during the process.

- 🥈 Silver (Bright Chrome): PERFECT. The shielding was intact until the metal cooled below its reactivity temperature. This level of perfection indicates maximum strength and ductility.

- 🌾 Light Straw/Gold: Acceptable. This indicates slight surface oxidation. For most industrial and commercial applications, this is a pass, and the colour can be removed with a Scotch-Brite pad.

- 🔵 Blue/Purple: Risky/Reject. Significant oxidation. The shield was removed too early or gas coverage was insufficient. For aerospace, this is a major fail. For other uses, the material properties are compromised.

- ⚪️ White / Grey Flakes: SCRAP. This is “Alpha Case”. The metal has become a brittle ceramic. There is no fixing this; the entire weld section must be cut out and redone.

Real-World Applications

Mastering the arc is one thing; applying it in the field is another. The definition of a “good weld” often changes depending on the industry context.

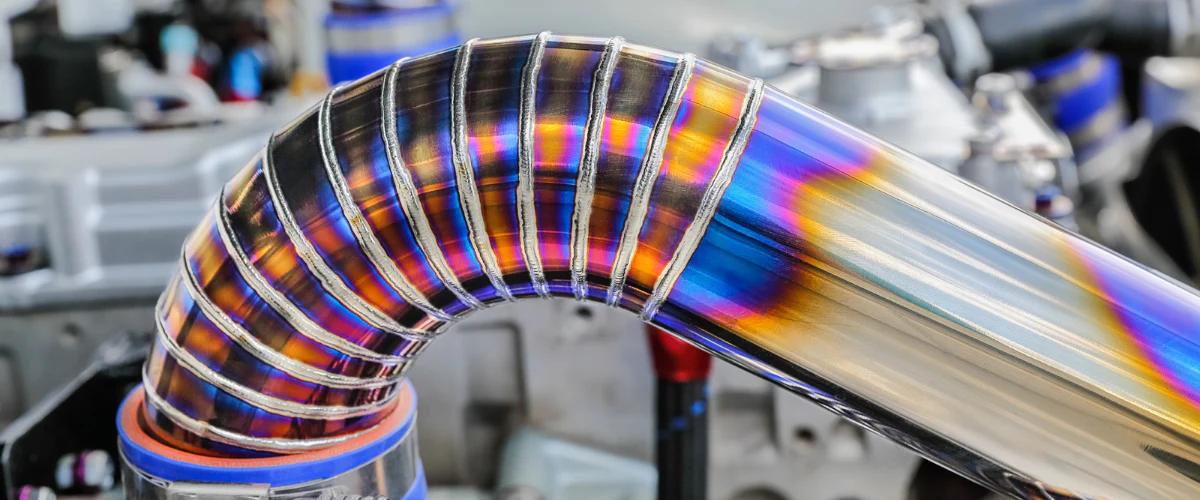

Automotive Performance: The “Pie Cut” Challenge In the fabrication of titanium exhausts and intakes, the focus is often on the artistry of “pie cuts”—welding complex bends from multiple segments. The biggest risk here is internal “sugaring” caused by poor back purging. While the outside might look like a perfect row of dimes, internal oxidation creates turbulence and leads to cracking under vibration.

Chemical & Industrial: Field Compliance For chemical plants handling corrosive media like chlorine, titanium is chosen for longevity. In this area, welding is often done in the field with local purge chambers (polyethylene tents) that make the conditions look like a cleanroom. Meeting ASME B31.3 standards is paramount, and color is strictly a compliance requirement, not an aesthetic one.

Marine & Offshore: Battling Crevice Corrosion Specialized applications often call for Grade 12 (Ti-0.8Ni-0.3Mo) or Grade 7 to prevent crevice corrosion in tight spaces like flanges. Fabricators must be vigilant to use matching filler wires; using a generic ERTi-2 wire on a Grade 12 flange will dilute the alloy, creating a weak point where corrosion will inevitably start.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Can I weld titanium to stainless steel?

A: No, you cannot TIG weld them directly. Titanium and iron form brittle intermetallic compounds that will crack immediately upon cooling. To join these dissimilar metals, you must use a mechanical connection (flanges) or a specialized explosion-bonded transition joint.

Q: Is titanium harder to weld than stainless steel?

A: Technically, the manipulation of the puddle is very similar to stainless steel; the molten pool is actually quite fluid and easy to control. The “difficulty” lies entirely in the discipline required for cleanliness and shielding. If you have a bad habit of dipping your tungsten or lifting the torch too soon, titanium will punish you instantly.

Q: How do I remove the blue discoloration?

A: It depends on the depth of oxidation. Light straw colors can often be removed with a stainless steel wire brush or Scotch-Brite pad. However, a deep blue or purple color indicates that the oxide has penetrated the surface. For critical aerospace parts, the result is a reject. For non-critical commercial parts, you may be able to grind it down until you reach bright silver metal, but you must verify that no alpha case remains.

Q: Why is my tungsten turning blue or purple?

A: This is a sign of insufficient Post-Flow. Your tungsten is still hot when the argon stops flowing, allowing oxygen to attack it. Increase your machine’s post-flow time (15+ seconds) or use the “Double Post-Flow” trick mentioned earlier. A contaminated tungsten will cause an unstable arc and wander.

Conclusion: Respect the Process

Welding titanium is ultimately a test of patience and discipline. It is often said that the process is 10% welding and 90% preparation. If you adhere to the strict cleaning protocols, invest in the proper gas lens setups, and obsess over your shielding gas quality, titanium will reward you with a component that is incredibly strong, lightweight, and permanent.

However, setting up a dedicated titanium cleanroom and qualifying welders to ASME standards is a massive investment in time and capital.

If you require high-precision titanium components—whether for custom automotive projects or critical industrial piping—without the risk of trial and error, HonTitan is here to help. We offer specialized fabrication services, delivering certified, X-ray tested, and ready-to-install titanium solutions tailored to your industry’s specific demands.

References & Further Reading

For more detailed information on standards, codes, and techniques discussed in this guide, please refer to the following resources:

TWI Global: Welding of Titanium and its Alloys (Job Knowledge 109) – For technical data on titanium reactivity and “getter” properties.

Welding Tips and Tricks: TIG Welding Titanium: The Bad Tank Reality – Real-world troubleshooting and practical shielding advice.

The Fabricator: The Facts on Welding Titanium – In-depth discussion on AWS D1.9 color acceptance criteria.

ASME: Process Piping Code B31.3 – The standard for chemical and industrial piping systems.